Palmyra - General Information

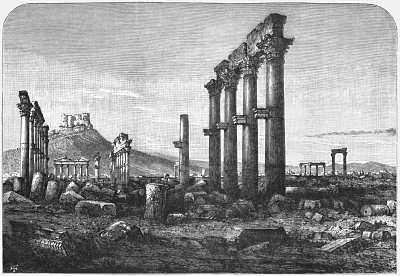

Palmyra, View Looking Down from the Western Castle Hill

After riding eleven hours the second day, we find the ranges of hills which border the broad valley suddenly approaching each other, the southern mountain sweeping to the northeast across the mouth of the valley. On the sides to the right and left are square towers. Some are low down, others on the summit of hills. These are the tower sepulchres of Palmyra . . . and as we emerge from the valley we see in the distance, on the top of the high northern hills, the castle, which commands the whole plateau of the City of Palms. From the west end of the castle . . . we are almost exactly in a line with the Great Colonnade, which seems in the distance like a forest of giant trees, stripped of their branches and bark by some fierce cyclone, and standing gaunt and naked against the sky. On every side are ruins, broken temples, towers, columns, tombs, and walls, in a tumultuous sea of stony fragments; and in the eastern extremity rises the stately Temple of the Sun, the finest ruin in Palmyra, and for extent and grandeur second to none in Syria. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 192.)

Palmyra, Temple of Bel, Eastern Side

“And Solomon built Baalath, and Tadmor in the wilderness, in the land.”—I KINGS ix. 18.

“And Solomon went to Hamath-zobah, and prevailed against it. And he built Tadmor in the wilderness, and all the store cities, which he built in Hamath.”—2 CHRON. viii. 3, 4.

In the former of these passages this city is called Tamar . . . and in the latter . . . Tadmor. The word Tamar in both Hebrew and Arabic means palm, or fruit, and Tadmor means probably “City of Palms.” The word Palmyra is simply the Latin translation of the Semitic original. The present name, and the only one by which it is known to the Arabic-speaking races, is Tŭdmŭr . . . . After the time of Solomon it is not even mentioned in history for nearly ten centuries. And it is a striking fact, that among the extensive ruins of the city there is not a wall or stone which can be identified as belonging to the era of the Hebrew monarch, the only approximation being the Hill of Balkis, Queen of Sheba, south of the sulphur fountain. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, pp. 201, 203-4.)

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 197

View of Palmyra from the Grand Colonnade, Showing the Castle in the Distance

Palmyra is an example of both the changing and the changeless in the East. Its name Tadmor remains. Its commercial importance is gone. The lines of national traffic have shifted from the Euphrates Valley to the Suez Canal and the Straits of Gibraltar. This once-glorious city, the seat of ancient commerce, the highway of the nations, the outpost of King Solomon, the key of Persia and India, the city of palaces, the home of Zenobia, the school of the sublime Longinus, built in remote antiquity, fortified and beautified by kings and emperors, is now, alas! a magnificent ruin. It stands in an oasis in the Syrian desert, about half-way between the Orontes and the Euphrates, and about one hundred and twenty miles east-north-east of Damascus . . . . Ancient writers describe it as a city of merchants, and proverbial for its wealth and luxury. It has been suggested that this Indian trade was the cause, in ancient as in modern times, of much of the military strife between the eastern and western nations, and that it occasioned the continual wars between Assyria and Babylon on the east, and Palestine and Phoenicia on the west. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, pp. 201-3.)

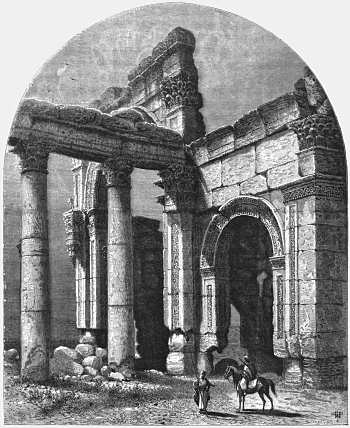

The Monumental Arch (aka Triumphal Arch), Palmyra

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 196

Palmyra is not alluded to in the history of the younger Cyrus or the campaigns of Alexander the Great. The decline of Tyre and Jerusalem, however, opened the way for the revival of the ancient city. Pliny says it was the first care of Parthia and Rome, when at war, to engage Palmyra in their interest. Mark Antony, during the triumvirate in 38 B.C., attempted to plunder Palmyra, on the ground of its having violated the neutrality between the Romans and Parthians. During the successive wars between these two great empires it increased rapidly in commercial and military importance, and became a wealthy and magnificent city. In 130 A.D. it submitted to Adrian, and, though nominally subject to Rome, had a senate and popular assembly of its own, as is seen from the inscriptions found among its ruins. Adrian adorned the city with many of its grandest temples and colonnades, gave it his own name, Adrianopolis, and conferred upon it the dignity and rank of a Roman colony. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 204.)

See Palmyra Grand Colonnade, Palmyra Temple of the Sun, Palmyra Tombs, Damascus, or Baalbek

At BiblePlaces, see Baalbek